Arguing Is Bullshit

It seems like all we do these days is argue. Woke stuff, Gaza stuff, blah blah blah.

What are we trying to accomplish with all this arguing? What does the word “argue” even mean? According to google, it means:

To give reasons or cite evidence in support of an idea… typically with the aim of persuading others to share one's view.

Hmm. So according to Google—and presumably other people—arguing is about persuasion. It’s about “giving reasons” and “citing evidence.” It’s about getting others to “share one’s view.” Hmm.

So, when we argue, like on the internet for example, we start out with different views. And the goal of arguing—its essential purpose—is for one or both of us to change our view. Hmm.

Should I say it? Okay, I’ll say it.

Here’s a list of problems with the idea that arguing is about persuasion:

Hitler. When people argue on the internet, they often compare each other to the German fascist. Which is an odd way to persuade someone. “Wow, I’m just like Hitler—you’ve totally persuaded me.” Odd sentence.

Shouting. We often raise our voices when we argue, which is also odd because people don’t like to be shouted at. If you upset the person you’re arguing with, they’re less likely to be persuaded. They might even run away.

Straw-manning. This is when you argue against a dumber, crazier version of the person’s view—a view that they do not actually hold. If arguing is about persuasion, then straw-manning is beyond odd. It makes no sense.

Echo chambers. Most of the arguments we consume are designed to confirm what we already believe, and most of the arguments we produce are directed at people who already agree with us. If the purpose of arguing is to get people to “share our view,” then why do most arguments occur between people who share the same view?

Nutpicking. This is when you focus on the dumbest, craziest arguments from the dumbest, craziest members of a group, thereby avoiding the possibility of being persuaded by anyone from that group. Which reminds me…

Why are we so reluctant to be persuaded? Shouldn’t we be pleased to be persuaded? After all, we learned something new. We changed our view and fulfilled the purpose of arguing.

People often don’t know what they’re arguing about. One person might define “socialism” as “Sweden,” while the other person might define it as “the Soviet Union.” Then they angrily talk past each other, failing to persuade each other of anything.

People often argue in abject ignorance. I constantly see people making lazy, sweeping arguments against the entire field of evolutionary psychology, for example, while lacking the most basic understanding of what evolutionary psychology even is.

And what about whataboutism? This is when you respond to someone’s argument about how bad your tribe is by launching a different, unrelated argument about how bad some other tribe is. It is unclear what this has to do with persuasion.

And what about all the fallacies? There’s the ad hominem fallacy (She’s cringe; therefore, she’s wrong), the appeal to authority (I’m credentialed, therefore I’m right), guilt by association (He has some asshole followers, therefore he’s wrong), the argument from incredulity (I cannot imagine how x is true, therefore x is false), and the argument from uncoolness (Believing x has uncool vibes, therefore x is false). Why would anyone be persuaded by this bullshit?

Then there’s the way we talk about arguing, as if it were war. We “defend” our claims against “attacks” from “the other side.” We talk about “strong” or “knock-down” arguments that are “devastating” to our “opponents.” But if arguing is about persuasion—the citing of evidence, the sharing of views—then the war metaphor is odd. Why not a show-and-tell metaphor, or a scouting metaphor, or a family-style meal metaphor, where we share our different views like plates of food?

Think about it. You’ve had many arguments throughout your life—some on the internet, some in real life. How often do these arguments end in someone saying, “Okay, you’ve persuaded me. I now share your view.” I’m guessing the answer is, “Almost never.” That is very odd for an activity supposedly centered on persuasion. Imagine I asked you how often driving gets you to your destination, and you said, “Almost never.” That would be very odd.

“But David you say, all this shows that people are bad at arguing. We really do want to persuade each other. It’s just really hard, and we’re dumb and irrational, and we don’t know how to do it right.”

Sorry, that’s bullshit, and here’s why.

Suppose I have a theory of friendship. My theory is that the purpose of friendship is sexual intercourse. You tell me my theory is obviously wrong because most of what friends do together has nothing to do with sex. I respond by saying, “All this shows that friends are bad at having sex with each other. Friends really do want to have sex with each other. It’s just really hard, and they’re dumb and irrational, and they don’t know how to do it right.” Obviously my response would be stupid. Form follows function, and if I’m claiming that a human activity serves a particular function, then the burden of proof is on me to show why the form of that activity fits the proposed function. If there’s no fit between form (friendship) and function (sex), then guess what? I’m wrong. I cannot wriggle out of being wrong by saying, “No we’re just really bad at having sex with our friends, you see.” If I always said stuff like that whenever you pointed to non-sexual aspects of friendship, then my theory would be unfalsifiable, and you would be right to call it bullshit.

The same is true of the theory that arguing is about persuasion. It’s a bullshit theory, and if you defend it by calling humans dumb and irrational, then you’re making the theory unfalsifiable. All of the examples above suggest that the form of arguing does not fit the function of persuasion. If anything, it looks like arguing is designed to prevent anyone from being persuaded of anything. If that’s true, then maybe we’re wrong about the function of arguing. Maybe persuasion—the citing of evidence, the giving of reasons—is not what we’re actually doing when we argue. Maybe that’s just a bullshit story we tell ourselves to cover up the real, darker purposes of arguing. Which brings me to…

The real, darker purposes of arguing

Allow me another analogy. Let’s say there are some donuts on the table, and you’d really love to have some.

Now imagine that every time you reach for a donut, a bunch of people yell at you, call you names, and talk about how only the worst kind of people eat donuts. If this kept happening to you in every donut-related situation, it would probably cause you to develop a fear donuts. Even if you really liked donuts, you’d probably wait until nobody was around before you reached for one.

Okay, now replace “reach for a donut” with “criticize our political tribe,” and you’ll begin to understand why arguing looks the way it does. The goal is not to persuade. The goal is to subtly punish people for questioning our dogmas or dissing our allies. When we argue about politics, we’re playing The Opinion Game—the secret war over social norms. And the norm we want to establish is: respect our tribe.

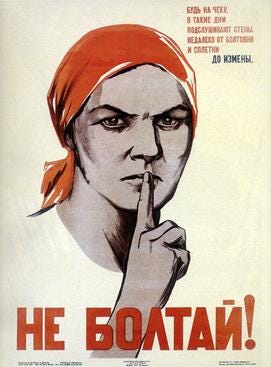

Think of the Soviet Union. Everyone secretly hates Stalin, but Stalin and his apparatchiks work very hard to prevent people from becoming aware of that fact. Because if everyone did become aware of their mutual hatred for Stalin, they would rise up to overthrow him. Bad news for Stalin.

So Stalin and his apparatchiks force people to parrot Soviet propaganda as loudly as possible, as publicly as possible, so that no one knows who the anti-Stalinists are, or how many anti-Stalinists there are in their midst. This prevents the anti-Stalinists from coordinating and rallying together. If anyone refuses to parrot the Soviet propaganda, or refuses to parrot it loudly enough—off to the gulags they go. Some version of this strategy is, to my knowledge, used by every authoritarian regime that has ever existed. It’s a very effective strategy for maintaining power.

In modern democracies, political coalitions aren’t as awful as the Soviet Union, but they ultimately want the same thing—i.e., to gain power, maintain it, and prevent others from taking it away. And they use similar (albeit milder) tactics. If people don’t parrot the coalition’s propaganda, or don’t parrot it loudly enough, they get “cancelled.” Getting cancelled isn’t as bad as getting sent to the gulags, but the outcome is the same. The opposition is silenced. The coalition maintains power.

Yea, it’s pretty dark stuff. Here are some other dark purposes of arguing:

We want to rally our tribe. Tribes are hard to rally. We need to create common knowledge that our tribe is the best and the other tribe is the worst. The problem is, the other tribe is constantly trying to prevent us from doing that by intimidating, silencing, and censoring us (see above). And we try to do the same thing to them, of course—it’s information warfare. So to escape the battleground, we create “safe spaces” or “echo chambers” or “news websites” where we can gather round and repeatedly chant in unison. OUR TRIBE IS BETTER THAN THEIR TRIBE. OUR TRIBE IS BETTER THAN THEIR TRIBE. This explains why most arguments are directed at people who already agree with us. The point is not to persuade; it’s to chant.

We want to rationalize. If our tribe is the best, then we wouldn’t support any bad policies or believe any stupid things, would we? No, we wouldn’t. If the other tribe is the worst, then they wouldn’t support any good policies or believe any reasonable things, would they? No, they wouldn’t. So to create common knowledge that our tribe is better than their tribe, we can’t just chant; we have to rationalize. We have to twist reality into group-flattering propaganda. The major obstacle to achieving this goal is reality itself. Reality can be very annoying.

We want to verbally spar. Arguments are a good chance to show off our skills—verbal, intellectual, social, moral—while exposing the inferior skills of our opponents. Presidential debates aren’t really about policy; they’re competitions to be quippier and more confident and more likable than the other candidate (just watch the post-debate analysis). This might explain why we don’t define our terms in advance of our arguments. The best tactic in a verbal sparring match is semantic jiu jitsu—the attempt to twist our opponents’ words against them. If we carefully defined our terms in advance, there would be no rhetorical weapons to deploy in the fight, and it would be a boring fight.

We want to defend our status. Behind every argument is the subtext, “I’m right and you’re wrong.” What could explain the fact that I’m right and you’re wrong? Well, it’s probably going to boil down to some version of, “I’m better than you.” Maybe I’m smarter, wiser, more reasonable—whatever the cause, it doesn’t make you look good. That’s why we don’t like being persuaded. To be persuaded is to imply that we are intellectually inferior to the person who persuaded us. Ouch.

We want to defend our tribes. More often, though, arguments are about the relative status of tribes. Insulting my tribe is like insulting me, and what do people do when they’re insulted? They fight back. They attack the other tribe—or any other tribe available—to preserve their relative standing, engaging in whataboutism. Which brings me to…

We want to attack others’ status. Given that status is relative, we can raise our own status by lowering someone else’s. This is basically the function of the quote tweet on Twitter/X. We make a snide remark about how stupid someone’s tweet is, thereby elevating our own tweet—literally and metaphorically—above theirs. Many of us eagerly scroll through our social media feeds looking for something, anything to take a dump on.

We want to cover up the fact that we’re doing all these dark, ugly things. When we overtly seek status, we lose status. Likewise, when our tribe overtly tries to intimidate rivals, silence dissidents, rationalize agendas, or chant in unison about our inherent superiority, our tribe looks bad, and we lose power. So to get away with all this ugliness, we need a cover story. We need some sweet-smelling, high-minded bullshit. So we disguise all our silencing, bullying, and propagandizing as—you guessed it—persuasion. We pretend that we’re engaging in “discourse” (where anyone who disagrees with us is automatically wrong), and that we want to have a “national conversation” (where everyone submissively echoes our dogmas). We put on a performance of “giving reasons” and “citing evidence,” to cover up the fact that we’re bullies and propagandists. We delude ourselves into thinking we’re on a noble quest to “change hearts and minds”—you know, by shouting at people and calling them Hitler.

What about the argument that arguing is bullshit?

Yes, there’s a contradiction here, so allow me to resolve it. I’m not saying that arguing is never about persuasion. It sometimes is. When we argue about mundane things like which restaurant we should pick for dinner, or what route we should take to get there, we really are trying to persuade, and we often succeed. In cases like this, we’re quite reasonable and willing to change our minds. For concrete, practical matters, we’re rational animals. For everything else, we’re apparatchiks.

To be sure, there are a small number of autistic-adjacent people that awkwardly bring this kind of concrete, practical rationality into politics—a domain where it doesn’t belong. But because autistic-adjacent people aren’t socially intelligent enough to recognize that politics is about tribalism and loyalty—and concealing the fact that it’s about tribalism and loyalty—they naively focus on facts and logic, and get frustrated by others’ unwillingness to share their focus. I’m guessing you probably belong in this category. You’re earnestly trying to play the persuasion game, while everyone else is trying to play the intergroup dominance game disguised as the persuasion game.

It’s time to introduce a new term into the lexicon: “pseudoargument.” A pseudoargument is a sparring match, status competition, tribal chant, or diss fight disguised as an attempt to persuade or be persuaded. The interlocutors might put on a performance of citing “evidence” or giving “reasons,” but lurking beneath the performance is something darker and uglier.

How can you tell if you’re in a pseudoargument? Here are some warning signs:

The person is not genuinely listening to what you’re saying and considering its implications.

The person does not ask you any questions and makes no attempt to get clarification on what you mean.

The person is arguing against positions you do not hold—positions that are far dumber and crazier than what you believe.

The person is interpreting what you say in the worst possible light.

The person is unwilling to acknowledge any valid points you make or mention any cases where they agree with you.

The person is angry, offended, or upset.

The argument revolves around issues that are central to the person’s tribal identity or social status.

The person is overconfident, talking about complex issues as if they were simple and alternative views as if they were crazy.

The person engages in whataboutism or deflection, focusing more on the relative status of people or tribes than the truth of propositions.

There is no sense of curiosity or mystery.

There is no sense of collaboration in getting to the truth.

It is unclear what is even being argued about.

The person interrupts you and would rather talk than listen.

The person dodges your questions.

Whenever the person’s views are on the brink of looking dubious, they change the subject.

Here’s my advice. If you find yourself in a pseudoargument, RUN! Get out of that situation. Nothing good will come from it.

Unfortunately, if you take my advice, you will find much of the internet off limits (except for the weirdly kind and reasonable comment section on Everything Is Bullshit). Real arguments are very hard to find on the internet: it’s mostly pseudoarguments.

Which sucks, because if you’re anything like me, you’re the kind of person who enjoys having real arguments (or likes to think they do). The kind of person who questions the nature of their reality and collaborates with other people to arrive at a fuller understanding of it (or likes to think they do). The kind of person who’s more troubled by political disagreements than outraged by them, who explains the world in terms of good and bad incentives instead of good and bad people. The kind of person with a healthy level of cynicism, informed not by resentment or despair, but by the clear-eyed recognition that we are animals—products of the Darwinian process—a lowly origin from which none of us are exempt.

If you’re anything like the person I’ve just described, then you probably think most arguing is bullshit too. You’ve probably felt it your whole life, haven’t you? The feeling that these so-called “arguments” of ours are not what they seem. If so, then I have good news for you. There’s a safe space here on Everything Is Bullshit. I look forward to arguing with you—genuinely arguing with you—very soon.

Heh. Positionality Statement: I do argue a lot, so perhaps I am simply being defensive and self-serving. Most of your analysis -- which I would say is generally spot on -- would say so.

And nor am I denying that I sometimes argue for just those reasons. Crushing my opponents?Lord there is something cool about that.

But I do have one big bad but. Or butt, depending on how you look at it. You know, arguers are often seen as assholes, so, big butt...

BUT! Arguing is also really useful, not so much for persuading others, maybe a litte, sometimes, but not mostly; it is useful for ME to get a better understanding of whatever issue I am arguing about. What are the critics of those taking an opposing view saying? Do they have ANY good points? Sometimes they do; even when they don't, understanding the criticisms is necessary to get a deeper understanding of why they are wrong or irrelevant. Sometimes, they bring new info to bear on the topic; and even if I conclude the new info they have brought is irrelevant or insufficient to change my view, I have learned something new that, sometimes, is worth knowing. And once in a while, maybe not in the heat of the argumentative moment, but after some time to cool down and let their views percolate, they do change my understanding of something.

Depth of understanding, knowledge, figuring out what is/is not truth, facts, especially in complex situations, or even figuring out ethics and morality (which I realize is also mostly bullshit), but here I am talking about for myself, not for anyone else, is at its best, when social processes, including debate, disagreement, arguing, function well. I do realize that social processes can also be disastrous, and I am not denying that. Exhibit A: The moral panic over racism the last 10 years. Lot beyond that. But my point is that social processes ALSO provide the best hope for figuring out which way is up. Or, to paraphrase Churchill, they are the worst way, except for all the others.

Uncharacteristically Constructively** Yours, Lee

**I do realize that attempts to publicly position oneself as constructive are probably mostly bullshit, but, still, as Winnie the Pooh might say, there you have it.

Great points. Just a side note, social behaviours can and mostly are coming from complex motivational systems. So instead of what is the function of A, the better question is what Are the functions of A and what is their order of importance based on evolutionary psychology. This question allows seemingly contradictory functions to coexist. Then maybe people are arguing for both tribal propaganda, verbal sparring, And persuasion. Itvis just that for most non autistic adjacent people persuasion is the lower priority