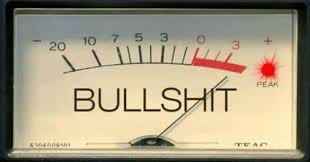

Bullshit Advice

We get it from self-help books. We pay consultants to give it to us in PowerPoint presentations. We hear it on podcasts about parenting, wellness, and professional advancement. Advice is all around us, but what is its purpose?

You might think the answer is to help us—to offer guidance and knowledge, to light our path and make us better people. The giving of advice is a noble and selfless act—humanity at its finest. Right?

Here’s a list of problems with the idea that advice is purely about helping us:

A lot of advice is baseless, but we want it anyways. We seek advice from famous actors on politics or the meaning of life, even though they’re not economists or philosophers. We gobble up Einstein’s vague advice about happiness, even though he wasn’t a psychologist.

A lot of advice is one-size-fits-all, even though people are different. “Be kind to yourself” is good advice for a perfectionist but bad advice for a narcissist. “Believe in yourself” is good advice if you’re talented but bad advice if you suck.

Much advice centers on goals we don’t really have—for example, how to be happy (even though happiness is bullshit), how to express your authentic self (even though authenticity is bullshit), or how to make the world a better place (even though we don’t really care about that).

Advice is rarely focused on the goals we actually have. For example, here’s what the self-help section might look like if it was focused on our real goals:

Zen and the Art of Social Climbing

Echo-Friendly: 10 Steps to Ensconcing Yourself in a Cocoon of Ideological Conformity and Motivated Reasoning

The 7 Habits of Highly Effective Virtue Signalers

The Lips 2 Butt Method: Take Control of Your Life by Sycophantically Ingratiating Yourself with High-Status People

Own It: Keep Rival Male’s Sperm out of Your Mate’s Vagina

You Can Do It! How to Harness the Power of Moral Ambiguity and Plausible Deniability to Rationalize Your Fucked-Up Behavior

Eat, Pray, Confabulate

A lot of advice is nearly impossible to follow. “Don’t be afraid of failure.” “Be happy with who you are.” But emotions are typically involuntary.

A lot of advice applies to all moments, even though moments are different. For example:

Hmm. What if the moment is 8:46am on September 11th, 2001?

A lot of advice is simple, even though the world is complicated. “Follow your passion.” “There are more important things in life than money.” But what if my passion is high-stakes poker and I’m living in dire poverty?

We are surprisingly uninterested in the effectiveness of advice. We rarely ask for track records of how often the advice worked out for people like us in situations like the one we’re in.

Much of the time, we don’t even know what to do with the advice we’re given. “Live life to the fullest.” “Keep moving forward.” It’s not obvious what behaviors are entailed by these vaporous slogans.

People almost never give advice like: “Distrust your instincts” or “Ignore what your heart is telling you.” But sometimes our hearts are foolish and our instincts are dumb.

Besides, what does it mean to listen to your heart or trust your instincts? It sounds like a nicer way of saying: “Do what you were probably going to do anyways.”

“But David,” you say, “Surely some advice is intended to help us. Surely some of it is helpful.”

Yes, don’t get me wrong—some advice is helpful. In particular, it can be helpful when the advisor has: 1) expertise about your situation, and 2) a stake in your success (e.g., they’re your family member or legal counsel).

But very few people have expertise about your situation, at least compared to you. And very few people have a meaningful stake in your success, at least compared to those closest to you.

And yet, most people would love to give you advice. They’re basically competing for that privilege on your social media feed every day, with all their tips and listicles and opinions about why you should do this or that. So there must be a lot of bullshit advice out there.

Why do we take it? Why do we give it? What is bullshit advice all about? I’m not sure, but here are my best guesses:

It’s about being superior. If I give you advice, I must be more intelligent, in-the-know, or successful than you. Otherwise, you wouldn’t need my advice. So advice has some awkward subtext: “I’m better than you.” This explains why we compete to give each other advice: it’s a kind of status competition. And it explains why we want advice from Einstein and other cool celebrities. They won the status competition, which means they won the right to give us advice, even if it’s vague and stupid.

It’s about status theft. How do you “steal” status? By giving someone advice when you’re equal or lower-status than them. People do that all the time, and when we’re on the receiving end of it, we feel annoyed or “condescended to.” It doesn’t matter if the person’s advice is objectively helpful and has lots of rigorous scientific research to back it up. That’s not the point. The point is they’re a status thief. They’re absconding with prestige.

It’s about ass-kissing. We often feel the urge to follow high-status people around and obey their every command. But when we do this too overtly, we come off as awkward, servile, and desperate. This is where advice comes in. It gives us an excuse to ambush a high-status person without creeping them out (“I was wondering if you had any advice about…”), and it gives us an excuse to submit to the high-status person without looking submissive (“I will take your advice to heart”).

It’s a kind of circle jerk. Obviously if I ask you for advice, I’m flattering you. “Tell me how to be awesome like you.” But what’s less obvious is that advice can also be flattering for the recipient. How so? Well, the recipient is usually presumed to have beautiful goals (like becoming a better person or making the world a better place), boundless potential for greatness, and magical powers like the ability to choose their emotions at will. And if the recipient has critics? Oh, those critics are just “haters” who hate things for no reason at all.

It’s about rationalization. Advice can be helpful in a perverse sort of way: it can function to justify or legitimize whatever the recipient wanted to do anyways. “Follow your heart.” “Listen to your inner voice.” My guess is this is a major function of consulting. It may also be a function of therapy. Often, the patient and the therapist work together to cook up a bullshit narrative—usually about childhood trauma—designed to rationalize the patient’s behavior. This might explain why so much advice is vague: it’s easier to contort vague advice to fit a pre-existing agenda than specific advice.

It’s about showing loyalty. In the midst of our various culture wars, giving advice can be like giving military aid: it can cement an alliance between the sharers. Giving you advice on how to raise antiracist children or embody Christ’s teachings or whatever—that signals we’re in the same political tribe. We share the same values. We’re playing the same status game.

Advice is like grooming

Many primates groom each other, removing bits of dirt, detritus, and dead skin from their fur. The original function of grooming was likely hygienic, designed to benefit the mutual groomers by reducing the prevalence of pathogens and parasites.

But this is not the only—or even the primary—function of grooming. It is also a kind of social ritual. Primates groom each other to forge alliances and navigate the political landscape. They groom each other to establish who is higher-ranking than whom, with lower-ranking individuals grooming higher-ranking individuals. Grooming is interwoven with the fabric of primate society, such that it is probably easier to predict grooming behavior with knowledge of the alliance structure and social hierarchy than with knowledge of whose fur is the dirtiest.

I think advice is similar. Maybe the original function of advice was to help us—just like the original function of grooming was hygienic. But advice has become interwoven with the fabric of social life. We give and take advice to signal loyalty and forge alliances. We use it to establish who is higher-ranking than whom. As a result, it is probably easier to predict the flow of advice with knowledge of the alliance structure and social hierarchy than with knowledge of who has—or needs—practical instruction.

In other words, advice isn’t really about helping us, any more than grooming is really about hygiene. Yes, advice can sometimes help, just as grooming can sometimes clean. But there is plenty of bullshit advice out there, just as there is plenty of needless grooming.

Pick your own fleas

A lot of thinkpieces end with a crescendo of bullshit advice. They tell you how to change the world or live a better life. The call to action is usually hollow and ritualistic. It’s the writer’s way of “grooming” the reader.

So to win some anti-status points, I will refrain from doing that. There’s no lesson here—no takeaway. I’m not even saying you should avoid bullshit advice necessarily. Maybe bullshit advice is just the thing you need right now! How should I know? I don’t know you. I have no expertise about your situation. And even if I had perfect knowledge of your idiosyncrasies and unique circumstances, I would have no stake in your success—no incentive to give you good (rather than good-sounding) advice.

Besides, you don’t need my advice anyways. If you’re reading these words, you’re probably living in a relatively well-off country with access to electricity, the internet, and plenty of leisure time to read blogs about bullshit. Which means things are going pretty well for you.

So, dear reader, it’s time to get out there and do what you do best: whatever you were going to do anyways.

Every time I read your stuff, it’s like getting a harsh reality check that stings, but in a good way because it seems to be full of truth.

From a personal perspective—do these cynical views of human nature bother you sometimes? Or do you have more of a “it is what it is,” attitude about it?

I know Everything is BS is the theme here, I’m just curious about some things that make you less cynical about people. Thanks for this piece. Big fan of the blog.

Love this one, nice work!