Utilitarianism Is Bullshit

According to google, utilitarianism is “the doctrine that an action is right insofar as it promotes happiness, and that the greatest happiness of the greatest number should be the guiding principle of conduct.”

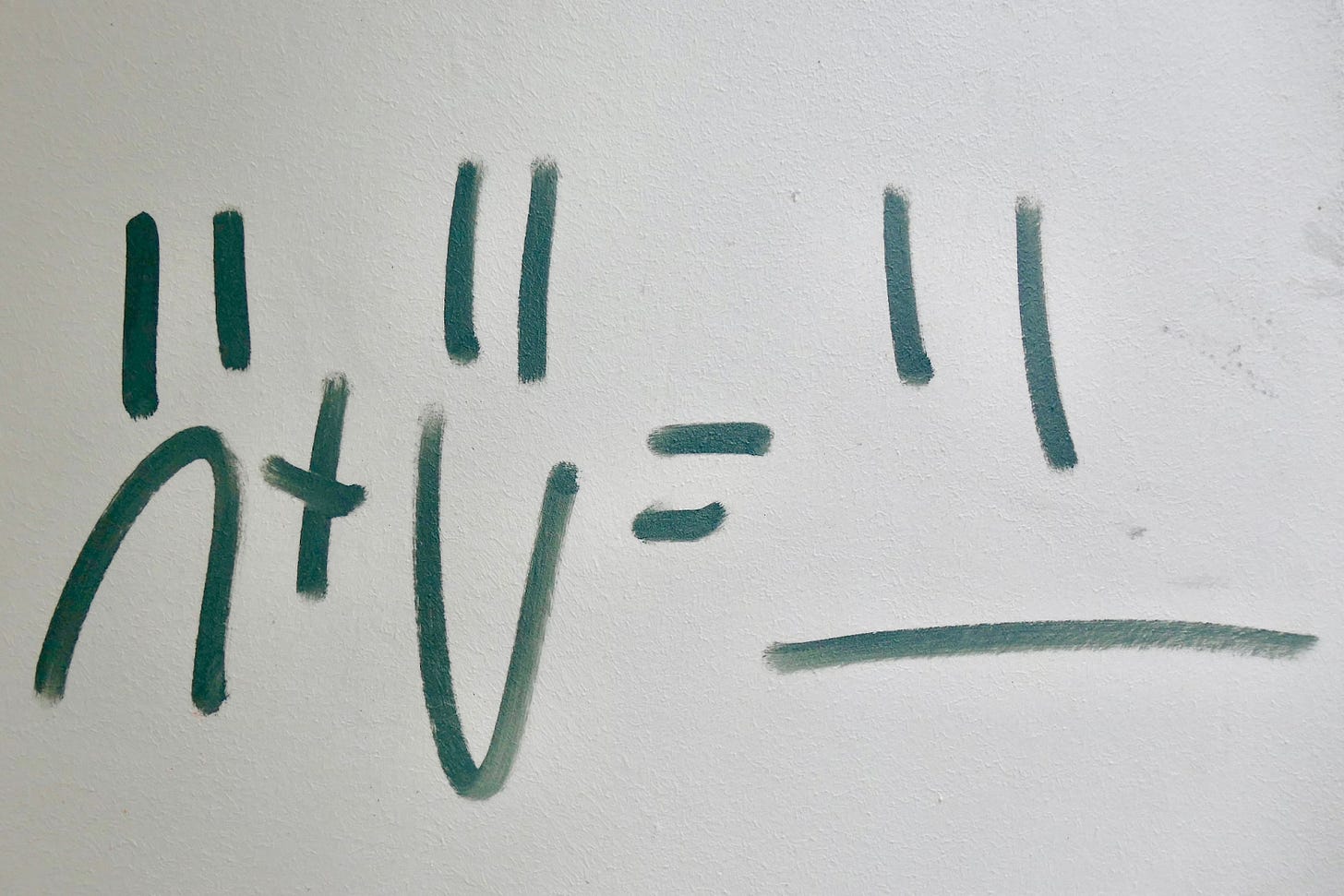

Translation: it’s morality for nerds. It’s the kind of ethics you do with math instead of vibes. If you’re trying to decide whether something is ethical, just crunch the numbers: add up the resulting happiness, subtract out the resulting pain, and if the number is positive, congratulations! You’ve calculated the “right” thing to do.

I used to be a utilitarian. You can probably see why it was appealing to me. It felt like a way to cut through all the bullshit—to stop blathering about justice and dignity and start solving equations. It implied that members of my nerdy subculture were morally superior to the masses, uniquely capable of transcending our primitive instincts and grasping the moral truth. We were rational; they were hysterical. We were effective altruists; they were virtue signalers.

But as I got older and wiser in the ways of evolutionary psychology, my confidence in utilitarianism faded, and I eventually abandoned it. Here’s how I changed my mind.

1) Happiness is bullshit

The first step was when I had a counterintuitive insight: humans don’t actually want to be happy. What we call “happiness” is a neural system that reorganizes the brain when there’s a prediction error—when things are bigger, cuter, juicier, or sexier than we expected. Like a “getting warmer” signal, happiness readjusts our expectations so that they’re more accurate the next time around. It rearranges our priorities so that they’re more aligned with how valuable—or worth pursuing—things are in the world. But it’s not the thing we’re pursuing. It’s not what we want.

Instead, we say we want to be happy as a confabulation, and many of us come to believe the confabulation—and even hold it sacred. What we’re pursuing is not good vibes in our heads, but the (often unflattering) things in the world that evolution programmed us to pursue, like sex, status, yummies, moral superiority, and high-status offspring. Instead of revealing the unflattering things we actually want, we say we’re pursuing happiness, because it sounds better.

My theory of happiness was hard to reconcile with utilitarianism. It felt weird to dedicate my life to maximizing something that nobody actually wants. And it’s not merely that we don’t want it: it looks like we’re trying to avoid it. A meta analysis of over 400 studies shows that the frequency and intensity of "positive affect” (i.e., happy or joyful states) steadily declines over one’s entire lifetime, starting at age nine. This makes sense if happiness is triggered by prediction errors: the more we experience the world, the more predictable it becomes. As I wrote in Happiness Is Bullshit, “We’re not pursuing happiness so much as chasing it away.”

So is chasing away happiness, the natural tendency of the human mind, morally wrong? Is the aging process a downward spiral of moral turpitude? Is being in a stable, predictable marriage ethically “worse” than having a wild, unpredictable string of sex partners, because the latter is more filled with prediction errors?

I didn’t know how to answer these questions. Even worse, it didn’t seem like there were “correct” answers.

2) Suffering is useful

The second step was when I started thinking about the evolutionary psychology of suffering. Suffering isn’t a pointless cloud of bad vibes: it’s a mechanism with a function. It evolved by natural selection to help us deal with bad things like injuries, infidelities, and failures. It compels us to avoid making the bad things worse and prevent them from happening again in the future. It’s the opposite of happiness, the “getting colder” signal—the thing that happens when we fall prey to a negative prediction error.

So a world without suffering would be a world where we aimlessly destroy our bodies and relationships, where we carelessly dig ourselves deeper and deeper into all of our problems, and where we stupidly repeat our mistakes over and over again. That doesn’t sound like a utopia. That sounds bad.

Besides, why should we try to get rid of something that most people (or 88% of people, according to this poll) don’t actually want to get rid of? Is it morally right to defy these people’s wishes and pump them full of opiates? Is it morally wrong to take our time with the bad things in life—to fully grieve the loss of our loved ones, to deeply regret the huge mistakes we’ve made—because it prolongs our suffering?

Again, I didn’t know how to answer these questions, and I doubted whether “correct” answers existed.

3) WTF are we even talking about?

After reflecting on 1) and 2), I realized that utilitarians suck at psychology. They have a crappy understanding of what happiness and suffering actually are. At least I’m trying to figure that out. At least I have a testable theory. The problem with utilitarians is that they don’t even try to come up with a testable theory. They just wave their hands and talk about vibes.

I used to have a lot of debates with myself about utilitarianism—inner dialogues where I tried to place the philosophy on a rigorous foundation. Here’s one of these debates, with me and an imaginary friend Util.

ME: So let’s be precise here. What exactly is this “happiness” thing you’re trying to maximize?

UTIL: It’s like, uh… feeling good.

ME: Okay, and what does it mean for a neural system to “feel good?”

UTIL: Well… I guess it’s like a qualia.

ME: Alright. What’s a qualia?

UTIL: It’s a feeling. Like the sensation of redness.

ME: And what makes a neural system a feeling?

UTIL: Nobody knows! It’s a total mystery. I can hardly wrap my head around it myself.

ME: So how do you know it’s real? Like how do you know this qualia thingy exists at all in the way you intuitively understand it?

UTIL: It just really seems like it. When I introspect, I’m like, “Whoa that feels good.”

ME: Okay, so you have a mysterious thingy in your head that seems to “feel good.” And why are we ethically obligated to maximize this thingy?

UTIL: Because it doesn’t just feel good. It is good. Like, intrinsically.

ME: Uh huh. And what does that mean?

UTIL: Like, it has value to the universe.

ME: Okay. And how do you know that?

UTIL: Well it just kind of seems like it.

ME: Uh huh. And how do you know you can lump them together? Like, how do you know your good qualia thingies can be lumped together with my bad qualia thingies to make neutral qualia thingies?

UTIL: It seems like it.

ME: And how do you know there’s a precise number of handjobs that can ethically outweigh a murder?

UTIL: Seems like it.

ME: Let me get this straight: you’re basing your entire ethical philosophy on vibes. On something that’s a total mystery. On a collection of seemings. With no empirical evidence to back any of this up. And no testable theory to describe what the hell you’re talking about.

UTIL: Yea.

ME: Weren’t you utilitarians supposed to be the hardheaded rationalists who were all about “science” and “logic” and avoiding appeals to intuition?

4) Desires don’t work either

At that point, the only way to maintain my utilitarianism was to abandon “hedonic utilitarianism,” the kind that was about happiness and suffering. But it comes in other flavors, like “desire utilitarianism,” where the thing to maximize isn’t happiness but desire satisfaction.

At first, this seemed like a good option. Obviously desires are real—they’re the things that move us—and we have some understanding of how they work. So why not base my ethics on those things? The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that desire utilitarianism was an ethical shit show.

Suppose I’m addicted to oxycontin. The addiction has ruined my life, and it doesn’t even make me feel good anymore because I’ve built up a huge tolerance to it. According to desire utilitarianism, the morally “right” thing to do is to pump me full of oxy. The more the better. In fact, if everyone on the planet got hooked on opiates, and we got robots to endlessly manufacture them for us, that would be a utopia—the pinnacle of human achievement.

The problems don’t end there. At least my opiate addiction doesn’t affect you: I can pop my pills and mind my own business and not bother you at all. But the problem with most of our other desires—the ones evolution gave us—is that they affect you. They affect everyone. What we mainly want is to be better than, or better off than, the people around us, because we’re competitive creatures. In fact if we can pull it off, we’d really like to dominate other people under a moral/religious pretext. That would be really awesome for us.

So the mathematically “best” world, according to desire utilitarianism, is a world where majorities dominate minorities under a moral/religious pretext—you know, the opposite of what we call “moral progress.” Since the majority is satisfied, and majorities are more numerous than minorities, the math comes out looking pretty good. And if we could trick the oppressed minorities into thinking their desires are being satisfied—say, by drugging or lobotomizing them—that would be even better. A moral improvement.

Come to think of it, if we could just trick everyone into thinking their desires were being satisfied—say, by lobotomizing the whole world, or by kidnapping everyone and plugging their brains into a dumb videogame where they’re constantly barraged with “1000 POINTS! GREAT JOB!”—that would be even better. Or if that fails, we can go the Orwellian route and shove propaganda down people’s throats until they love Big Brother and sincerely believe they’re living in a utopia—you know, the opposite message of 1984.

Or wait, maybe we should rethink all this and declare, based on nothing, that what matters is objective desire satisfaction in the world outside our heads, regardless of whether anyone feels satisfied. In that case, we’d be obligated to satisfy the racist, sexist desires of our ancestors—or reach some sort of moral compromise with them—even though they’re dead and feel nothing.

Lots of fun options here.

5) Do utilitarians even exist?

The more I thought about what morality is and how it evolved, the more I realized there is no way our actual moral intuitions are utilitarian. Utilitarian morals are unevolvable.

Organisms do not evolve to act for the good of the species. They evolve to act for the good of the genes that constructed them and against the genes that constructed their rivals. Or at least, we are more likely to be descended from such organisms—more likely to carry their genes inside us than the genes of their outcompeted rivals. As I’ve written about before, a proper understanding of genetic selfishness should make us more cynical about human nature—and especially human morality.

Utilitarianism cannot survive such cynicism. Any organism that was driven to maximize the happiness of all sentient beings, with no partiality toward itself, its kin, or its allies, would be a Darwinian dead-end. Our deepest values are not—and could not possibly be—utilitarian.

So when people tried to claim that utilitarianism fit all their moral intuitions perfectly, I realized they must be bullshitting. They were pretending to have values they did not have—or at least, not deep down.

This became especially apparent to me after reflecting on all the hypothetical scenarios that philosophers dreamt up to attack utilitarianism. You’re probably familiar with some of them. The “utility monster” that gains more happiness from eating your children than they get from being alive. The “trolley problem” where you can violently hurl a fat man’s body in front of a runaway trolley, killing him to save the lives of five other people in the trolley’s path. The doctor who kills you and harvests your organs to save the lives of five other patients in need of transplants. The list goes on.

If you present a utilitarian with any one of these moral “gotchas,” they’ll nearly always try to wriggle out of it. “You didn’t imagine the scenario right,” they’ll say. Or: “The scenario doesn’t count because it would never happen in real life.” Or: “Even if it would happen in real life, there are all these other considerations [insert tons of frantic hand-waving] that aren’t in the scenario that would still make it wrong.”

I’m not even disagreeing with the frantic hand-waving. Maybe some of it is cogent. But the fact that utilitarians are waving their hands—desperately trying to wriggle out of these moral gotchas—reveals that their intuitions aren’t really utilitarian. If they were, there would be nothing to wriggle out of. “Yea, of course I’d throw my children into the utility monster’s mouth. It’s obviously the right thing to do.”

7) In denial of human nature

At this point, the utilitarian might reply, “Fine, maybe my intuitions aren’t really utilitarian deep down. Forget about my intuitions then! They’re dumb, they’re primitive caveman instincts, let’s abandon them in favor of the utilitarian calculations.”

That’s all well and good, and it’s a move I considered making. But I ultimately realized it was stupid.

Isn’t utilitarianism also based on intuitions? Like the intuitions about mysterious qualia thingies that neatly aggregate across different people’s minds and have a numerical value to the universe or something? What makes those intuitions better than my other intuitions?

And besides, even if I did want to abandon my other intuitions, how can I explain the Darwinian function of that desire—the desire to abandon my other intuitions? That desire cannot be utilitarian, because such a desire is unevolvable. So it’s probably some kind of status-seeking tactic—a desire to show off how “rational” I am to my nerdy peers. Why is that unflattering desire better than any of my other desires?

Also, do I really think I’m going to get people to abandon their moral convictions in favor of some bullshit calculation I made up? Who do I think I am? If I’m going to make compelling moral arguments to real-life humans who are not in my nerdy subculture, I have to meet them where they are. I have to reckon with human nature, because human nature isn’t utilitarian, and it isn’t going away any time soon. Also, I have to reckon with the human I am, because I’m not going away any time soon. What I ultimately realized was that utilitarians are a bunch of humans pretending they’re not humans to look cool.

In search of a new morality

With utilitarianism out of the picture, what did I replace it with? You might think the answer is nihilism. Nothing matters, morality is a delusion. I did express sympathy with that idea here. And it fits my vibe.

But I’m not a moral nihilist, though I used to be. I waffled between nihilism and utilitarianism for the past five or ten years, switching back and forth between them and occasionally holding on to both at the same time—a kind of nihilistic utilitarianism where “nothing matters but I personally want to maximize utility just because.” Kind of a weird philosophy, I know, but it made sense to me at the time.

But I now have a new ethical worldview I’m more confident about. It’s a kind of moral naturalism. Here’s the gist if you’re curious.

The keys to morality

According to my new view, moral judgments are about the specific kinds of situations that our moral emotions evolved to detect. Just as a smoke alarm is designed to detect smoke, anger is “designed” by natural selection to detect unfair treatment, compassion is designed to detect potential exchange partners in need (the greater the need, the greater the IOU), shame is designed to detect—and cover up—things that make us look bad, social disgust is designed to detect others’ shameful acts and traits (so we can avoid being “contaminated” by them), and hatred is designed to detect negative correlations between our biological fitness and someone else’s. I’m oversimplifying a bit—emotions are complicated—but you get the idea.

Here’s the point: it is possible to be objectively wrong about these things. Our emotions can misfire. We can think we were treated unfairly when we actually weren’t. We can think we should be ashamed of ourselves when we actually shouldn’t be. We can hate a group of people when they pose no threat to us. If we were mistaken, then the emotion—e.g., anger, shame, hatred—was in error. It got fed bad information, or it got exploited by some bullshitter or propagandist. There’s nothing to be mad about. There’s nothing to be ashamed of. There’s no reason to hate these people.

I eventually realized that when I used moral language, this was the sort of thing I was talking about. This was what I meant when I said things like “x is gross” or “x is evil.” I meant something like “x is the sort of thing that objectively fits the inputs for social disgust” or “x is the sort of thing that could not fail to activate outrage, loathing, and contempt in any normal human with access to all the relevant information.”

So that’s what I think morality is now. It’s the stuff that objectively triggers our moral emotions, in the same way that keys are the things that objectively fit locks. Yes, we’re extremely biased about morality, and we often exploit others’ moral emotions for nefarious purposes (which I’ve written about here). But at least I know what morality is now. At least I know what I’m talking about when I use words like “right, “wrong,” “good,” or “evil”

And I think it’s what you’re talking about too when you use these words. I even think it’s what utilitarians are talking about when they moralize shrimp welfare or longtermism or whatever. When utilitarians say their philosophy is the “moral truth,” they mean something like:

Utilitarianism objectively fits the locks of our moral and epistemic emotions, which means that any normal, unbiased person with access to all the relevant information would inevitably realize that maximizing utility is the only thing that matters in life. Non-utilitarians must therefore be missing something, or else be biased, immoral, or stupid.

Of course, the claim is bullshit. It’s just a strategy for winning The Opinion Game and creating a new social norm where pretending to be utilitarian wins you status points. But even if the claim is bullshit, it is what utilitarians are saying (or implying), whether they realize it or not.

Let’s not get carried away

Now I don’t mean to say that utilitarian concerns are ethically irrelevant. It’s obviously bad to hurt people. It’s good to help them if you can. Torturing animals is bad. When adjudicating between policies, or evaluating charities, or deciding which incentive structures to implement, utilitarian considerations are indispensable.

And of course, our moral intuitions are partly utilitarian. The human mind evolved to care about things like “number of people pissed off with me” or “number of people indebted to me.” From a Darwinian standpoint, these are important things to consider when making decisions.

What I’m saying is: utilitarianism isn’t everything. It’s not the purpose of life or the apotheosis of ethics. It’s not the only thing that matters to normal, reasonable, well-meaning people with access to all the relevant information. Ethics is complicated. Humans are complicated. We cannot reduce our emotional life to a simple formula.

At the end of the day, our feelings do not tell us where they come from or why they exist. The only way to figure that out is to do some evolutionary psychology. I’ve done a bit of that myself, and I can tell you: the truth isn’t pretty. Our ethical lives are, in large part, about competing for moral superiority while disguising the fact that we’re doing that—a disguise that is, itself, part of the competition. Utilitarians try to be morally superior to the rest of us, and in some cases, they succeed. In other cases, they fail.

We’ll all keep jockeying for virtue points for as long as our species exists. It’s what we do. Maybe all this moral peacocking will contribute to moral progress—the erosion of tribal hypocrisy and propaganda—or maybe it won’t. As a wise man once said, “The arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward status.”

I agree with you. But I'll also be a pedantic mathematician and go further to say utilitarianism fails well beyond these considerations.

The appeal of utilitarianism is also in its quantification of preferences for modeling purposes - considering economic actors as making decisions by maximizing utility, and, correspondingly, impartial adjudication of different incentive structures in the context of microeconomic and social choice theory for the purpose of designing institutions.

And it falls flat here, too.

1) As you note people don't actually have closed form utility functions, and a better microeconomic theory of market decisions is maximizing cumulative prospects, which is the sum of gains from some reference point.

2) Within the field of Welfare Economics, the study of technical formalism on social well being, utilitarianism suffers from various gotchas, and it's not taken seriously in formal Economic Theory. Among various competitors, I prefer (the Nobel Prize winner) Amartya Sen's framework of maximizing capability vectors, that is the variety of possible options the people in a polity have - consume goods and services, start a business, engage in community involvement, etc.

Moral particularism > utilitarianism (and consequentialism)