Manufactured niceness

From corporate philanthropy to woke capitalism

Note from David:

This is a guest post from Lionel Page, a behavioral economist at the University of Queensland and blogger at Optimally Irrational. Lionel is one of the best examples of an incentive determinist I’ve yet encountered—someone who thinks about good and bad institutions, as opposed to good and bad people. In this post, he applies incentive-based logic to a topic near and dear to my heart: corporate bullshit. Enjoy.

If there’s one thing that free-market economists and anti-capitalist activists can agree on, it’s that corporations aim to make money—that’s their goal. And yet, if you look at the mission statement of any large corporation, it won’t say: “Our mission is to make as much money as possible.” The same is true of a business’s “values.” If you go on Microsoft’s website and click “What we value”, you will not find the one-word sentence: “Money.” Instead, you will see a variety of words about “diversity,” “respect,” and “integrity.”

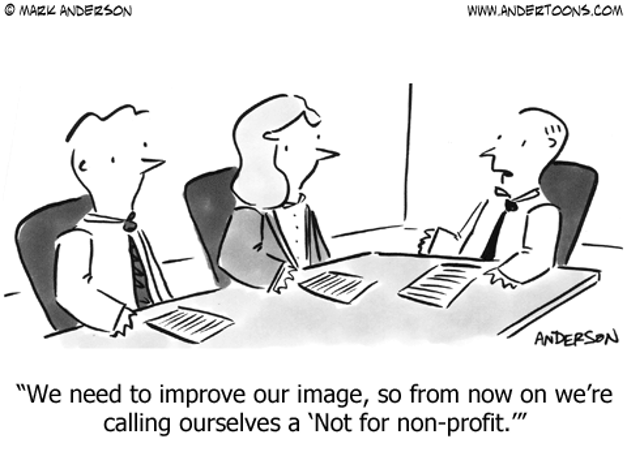

Nowadays, many companies seem to have taken to heart the idea of being nice—to help their employees, customers, society, and the environment at large, regardless of profit. Many even give away some of their profits to charity. Of all the things a company might manufacture, why niceness? What is going on here?

One answer is that manufactured niceness is what David calls a “social paradox.” What looks like giving away money to good causes is actually just another kind of profit-seeking. Maybe corporate philanthropy ultimately increases profit by currying favor with consumers and increasing brand loyalty. Or maybe it boosts morale within the company, giving employees the “warm glow” of altruism and increasing their productivity. The paradox is that in order to selfishly make money, you must (appear to) not care about selfishly making money.

And there’s some truth to this. Research on corporate philanthropy suggests that profit-seeking is indeed an (unstated) objective of corporate philanthropy: “Many firms have discovered the performance benefits of philanthropy, including increased customer loyalty, enhanced company reputation, and strengthened employee commitment and reputation” (McAlister and Ferrell, 2002).

A more sinister explanation is that corporate do-gooding may sometimes be designed to deflect blame away from other company activities that may be harmful, while gaining the political power to continue engaging in those harmful (and profitable) activities. Firms from the tobacco and petrol industries have, for instance, given to social causes and political parties likely to counteract the negative publicity around their activity and to gain political influence.

Another possibility is that managers engage in corporate philanthropy to boost their social status using company money. It is a case of the principal-agent problem whereby managers use their discretion to extract benefits from their position without maximizing the firm’s value for shareholders.

Managers divert "discretionary profits"… to finance the consumption of various preferred expenditures: unnecessarily luxurious office suites, excess staff, lavish expense accounts, salaries above those necessary to retain managers, and the like… corporate contributions may fit into the managerial discretion framework… as a preferred expenditure designed to boost the manager's prestige in the community or, more altruistically, simply as a way to generate the warm glow of the "performance of office for the benefit of society” - Navarro (1988)

One of the possible gains in status associated with corporate philanthropy is the gain in “respectability from the [local] elite” (Galaskiewicz, 1985). In short, managers can raise their status among their business and political elite by engaging in publicly visible charitable activities.

This interpretation is supported by a study from economists Mazulis and Reza (2014) who found no significant impact of corporate philanthropic spending on profits, but evidence that companies give more to charities with which the CEO has personal connections—that is, CEOs are diverting company money to their connections in the nonprofit sector. Another telling finding of the study is that companies give less when their CEO has a larger share of ownership of the company (and hence more “skin in the game”).

CEO charity connections—an observable measure of charity preferences—raise both the likelihood and amount of corporate giving by 21.5% and 1.5%, respectively, whereas a 10% rise in CEO ownership reduces the likelihood and amount of corporate giving by 40% and 3%, respectively. - Mazulis and Reza (2014)

The upshot of these results is that corporate philanthropy is likely distorted by the managers’ incentives to build their personal brand and connect with other movers and shakers. It is easy to be generous when you’re spending other people’s money.

Woke capitalism

Over recent years, large companies have moved beyond philanthropy and into a new arena: political ideas. They have incorporated themes of social justice into their branding, product design, and hiring practices. This politicization has been especially surprising for managerial professions that have traditionally been seen as conservative. This trend has been labelled “woke capitalism.”

The reasons why companies moved into politicized discourse are less straightforward than the corporate philanthropy case, but the same dynamics are likely at play. First, companies may think that it will increase their bottom line by adopting a social message that appeals to their market audience. In that view, woke capitalism is just another form of marketing. This might explain why brands strategically tailor their political philosophy to the countries they are advertising in. For example, consider companies’ use of the rainbow flag during gay pride month. If you look at the logos below, you’ll see that companies are willing to courageously fight for LGBT rights… in places where that fight has already been won.

The embrace of social justice themes by large corporations has generated a pushback in conservative circles where “woke capitalism” is decried as being bad for capitalism.1 And indeed, some brands have faced a backlash from venturing into social justice themes. The most prominent case has been the organised boycott of Bud Light beers in 2023 after the company used (in a somewhat marginal advertising campaign) a transgender person as an icon for the brand.

Then again, pushing against the idea that woke capitalism is bad for business, BlackRock chairman and CEO Larry Fink stated that stakeholder capitalism “is not about politics. It is not a social or ideological agenda. It is not ‘woke.’ It is capitalism, driven by mutually beneficial relationships between you and the employees, customers, suppliers, and communities your company relies on to prosper.”

That sounds pretty good, but there is a catch in this vision of “stakeholder capitalism”: these stakeholders are not really at the table to decide how capitalism should be managed. Representatives of “employees, customers, suppliers, and communities” are not on the executive boards of major companies in any noticeable way that would allow them to influence companies’ decisions. If companies were really implementing “stakeholder capitalism” they would change their governance structure to give real oversight to people representing a broader range of interests than those of the shareholders and the managers. There is nothing like this in sight.

In that perspective, “woke capitalism” appears again, at least in part, like a case of managerial capture whereby social justice branding increases the public profile of managers who may be investing not just in their companies’ image but in their personal image.

This managerial capture goes beyond the corporate philanthropy case though. By investing in politics, some on the left are concerned that managers are replacing democratic political processes. This is the perspective of Carl Rhodes in his book Woke Capitalism. How Corporate Morality is Sabotaging Democracy (2021).

Cloaked in the apparent moral glow of self-righteous and often facile political positions, civic debate and democratic dissent are replaced with the self-congratulatory slickness of marketing and public relations campaigning… Woke capitalism is a subterfuge for the corporate takeover of democracy. It is a means through which private companies are trying to take political power away from government and put it in their own hands. - Rhodes (2021)

Within the narrower setting of firms themselves, there is also a sense in which the politicization of corporate activities infringes on citizens’ democratic rights. Firms are not democracies, but top-down organizations where managers have a lot of leverage to influence employees’ social success (e.g. firings or promotions). Once a company’s management embraces a political position, it curtails (either explicitly or de facto) the ability of employees to voice their opinions freely on that matter. While corporate philanthropy’s cost is mainly borne by shareholders, whose money is diverted toward the CEO’s pet causes, woke capitalism’s cost is mainly borne by employees who lose their democratic right to express their views publicly.

In short, the vanilla capitalist manager was already annoying enough when trying to make you work on the weekend. The woke capitalist manager is now moving on to control what you can write on Twitter too.

Is it bad to have more responsible corporations that embrace “stakeholder capitalism,” and principles of “environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG)?” Not on principle, but as long as corporate firms’ governance is structured around shareholders’ and managers’ interests, we can expect corporate social kindness to primarily advance the interests of those implementing it—even if it comes at others’ expense.

References

Friedman, M., 1962. Capitalism and Freedom. The University of Chicago Press.

Galaskiewicz, J., 1985. Social organization of an urban grants economy: A study of business philanthropy and nonprofit organizations. Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Gautier, A. and Pache, A.C., 2015. Research on corporate philanthropy: A review and assessment. Journal of Business Ethics, 126, pp.343-369.

Masulis, R.W. and Reza, S.W., 2015. Agency problems of corporate philanthropy. The Review of Financial Studies, 28(2), pp.592-636.

Navarro, P., 1988. Why do corporations give to charity?. Journal of business, pp.65-93.

Ramaswamy, V., 2021. Woke, Inc.: Inside corporate America's social justice scam. Hachette UK.

Rhodes, C., 2021. Woke capitalism: How corporate morality is sabotaging democracy. Policy Press.

Thorne McAlister, D. and Ferrell, L., 2002. The role of strategic philanthropy in marketing strategy. European Journal of Marketing, 36(5/6), pp.689-705.

In an interesting re-organization of social coalitions underlying political fault lines in Western countries, conservatives now often criticize the “economic elites” as acting against “the people”. In his book Woke Inc (2021) the US presidential candidate Vivek Ramaswamy describes woke capitalism as “bad for America” and as reflecting the oversized influence of the “managerial class”.

This was a good analysis. I have come to see Lionel Page, David Pinsof, and Dan Williams as forming a category of interesting truth-seeking philosophers on Substack. Pinsof is still probably my favorite due to his darkness and cynicism. A David Pinsof essay makes Cormac McCarthy's "The Road" look like Barney and Friends.

I worked for a few years for a Polish branch of an US corporation that heavily pushed the DEI agenda. FYI Poland is pretty conservative compared to US, the woke views are typically considered fringe and outlandish up here. There is only one leftist party which parrots the US woke narrative with ~10% of the popular vote (mostly from women 25 and under).

Sometimes, I would see managers from my company bragging about going to Gay Pride parades on social media and I be like: "WTF are they doing? Are they gay? They have wives!". Now, I kind of get what was the game they were playing.

Also, the stakeholder capitalism part sounds a lot like how Rob Henderson described self-proclaimed minority activists at elite universities ( https://nypost.com/2024/02/17/us-news/foster-kid-who-went-to-yale-says-family-trumps-college/ ):

>> We should be skeptical of the people who claim to speak on behalf of these communities.

>> Instead of looking to self proclaimed leaders of various marginalized and dispossessed groups, we need to actually ask those groups themselves.

>> It’s worth collecting data, looking at surveys, speaking with people — not just community leaders and activists who have their own agendas.

>> I saw this at Yale where someone who shares the characteristics of a historically mistreated group would claim to speak on behalf of them, but they had very little in common with them other than the way that they looked.

>> I want people to be a bit more skeptical of the self-proclaimed activist leaders who could be trying to push an agenda, trying to elicit sympathy, and trying to exploit people’s concerns.

Both this and the stakeholder capitalism could be framed as a single problem called "woke activism" and then discussed separately to expose, attack and destroy the status game these people are playing.