AI Doomerism Is Bullshit

THE ROBOTS ARE GOING TO KILL US ALL!

Or at least, that's what the AI doomers are saying. Some are more confident about it than others, but all agree that the probability of an AI apocalypse, known as "p(doom)," is alarmingly high.

How is, say, GPT-7 going to annihilate us? Doomers don’t really know. They don’t have a single murder weapon in mind or a specific doomsday scenario they’re preparing for.

Instead, they gesture at the type of thing a rogue AI might do. Maybe it will design and manufacture superpathogens. Maybe it will hack into military databases to launch all the nuclear weapons. Maybe it will gun us down with murderbot drones.

Obviously I think this is bullshit or I wouldn’t have inserted Homer Simpson. But Al doomerism is unlike other bullshit I’ve written about on this blog. It defies every stereotype about what bullshit is and where it comes from. It scares me, not because I’m scared of getting nuked by ChatGPT, but because I’m scared of epistemic nihilism—the idea that the search for truth is hopeless for apes like us.

You see, doomers are brilliant. They’re among the most thoughtful and explicitly truth-obsessed apes on the planet. They’re behind the rationality movement and effective altruism—brainy endeavors to think more clearly and quantify charitable impact. They avoid every logical fallacy and dream in Bayes theorem. If anyone is going to be right, it’s them.

How could this have happened? How could people so scrupulous—so dedicated to purging their minds of bullshit—fall prey to it in its most lurid, apocalyptic forms? Am I the crazy one here? Is there really a decent chance I’m going to be gunned down by a swarm of murderbots or something?

I’m a longtime fan of rationality and effective altruism. I’ve been following these fields for my entire adult life and generally agree with their takes on animal welfare, climate change, scout mindsets, and helping the global poor. But not AI doomerism. One of these is not like the others.

For a while, I assumed I was missing something. Maybe there was an argument I hadn’t yet heard. Maybe some AI horror story would unfold and scare me straight. I kept waiting for a thoughtful person to bring in the missing piece of the puzzle—to teach me how to start worrying and hate the bot.

It never happened. Every time the topic came up on podcasts or in person, I’d end up banging my head against the table. Doomers often encroach on topics related to evolutionary psychology—a field I have a PhD in—and their level of understanding there is… inadequate. I eventually came to the sad conclusion that I was not missing something. They were missing something. They were missing this post.

What is this post? I wish it were something like this:

But it’s actually more like this:

This post is long. Probably too long if I’m being honest. But if you’re scared of dying at the hands of a robot, or simply curious about how “rationalists” could be so irrational, this post will be worth your time.

AI doomerism in a nutshell

Part of the appeal of AI doomerism is its simple, commonsensical vibe. We all know what “intelligence” is. We all know it’s humanity’s superpower. Now imagine that superpower in a robot. Sounds pretty scary!

But don’t be fooled by appearances. Behind the commonsensical vibe is a leaning tower of questionable assumptions, built atop a quicksand of tempting-but-misleading intuitions. Doomers rarely lay out their assumptions explicitly, which means I’ll have to do it for them. As I see it, they’re making at least eleven claims:

Intelligence is one thing.

It’s in the brain.

It’s on a single continuum.

It can help you achieve any goal.

It has barely any limits or constraints.

AIs have it.

AIs have been getting more of it.

An AI will soon get as much (or more of it) than us.

Such a (super)human-level AI will become good at every job.

And it will become good at ending humanity.

And it will want to end humanity, because ending humanity is a good way to achieve any goal.

Okay, not so simple anymore. Let’s take a closer look at each assumption.

1. Intelligence is one thing.

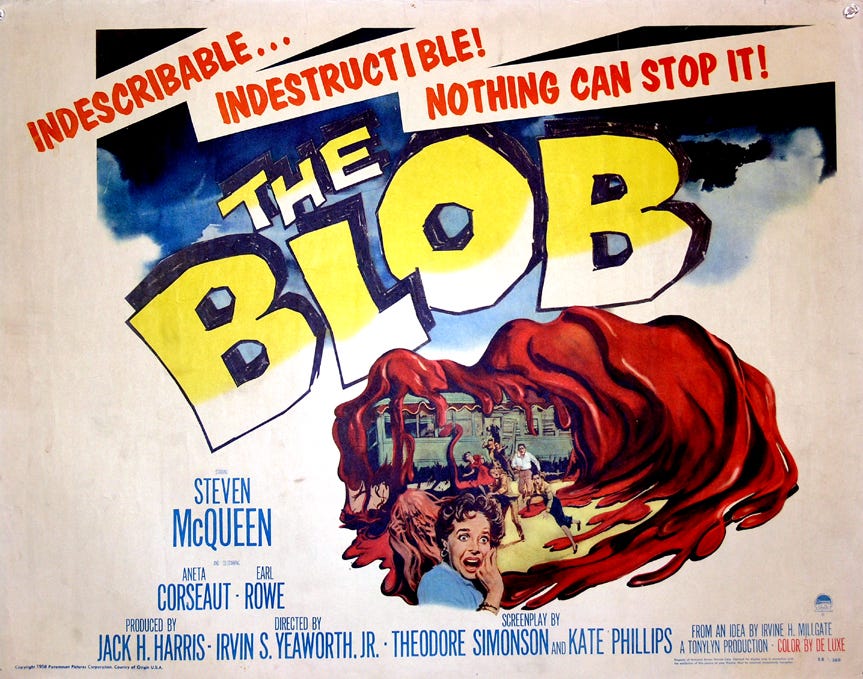

Seems like an innocent thing to say. What makes a person smart? Intelligence. What’s intelligence? A singular noun. What’s it made out of? Meh, nothing special. Doomers think it’s pretty straightforward—a simple learning algorithm trained on a shitload of data. Scott Alexander variously refers to it as a “blob of neural network,” “blob of intelligence,” or “blob of compute.” Talk of an “intelligence explosion” implies the blob can make itself bigger and bigger until it envelops the planet, like in that campy movie from the 50s.

Okay, fun stuff. But what if it’s bullshit? What if, when we talk about “intelligence,” we’re not pointing to a singular, spooky substance, but unknowingly gesturing at a wide variety of complex, heterogeneous things?

For example, attention. You’re paying it. Your brain is choosing which stuff to focus on, like the meaning of these words, and which stuff to ignore, like the feeling of the clothes on your back. Is that “intelligence?”

And you have stuff to focus on, like sights, sounds, words, clothes, and backs—all of which fluidly interact with each other, as when the words “clothes on your back” make you feel the clothes on your back, or when the feeling of the clothes on your back makes you briefly ignore these words and scratch your back. Is this undulating web of sensations—your flow of awareness—“intelligence?”

And you can do things with this flow of awareness. You can continue reading these words or subscribe to this substack or scratch your back or order a backscratcher on Amazon or suddenly panic about a deadline or call your boss or sign a docusign or open a package or assemble a desk chair or frantically unscrew the thing you just screwed in. How much of your behavioral repertoire is “intelligence?”

And you have an imagination. You can simulate how things might play out in your mind’s eye and use these simulations to figure out your next move. Is that “intelligence?”

And you can differentiate your imaginings from reality—something AIs have a hard time doing. Is that “intelligence?”

And you have common sense. You know that requesting information from a real person named “Dana” is different from requesting information from a new username you created named “Dana”—unlike AIs, apparently. Is that “intelligence?”

And you have complex motivations. They move your body, attention, and imagination over the course of days or decades, in the face of obstacles and setbacks. They’re moving you right now. Is that “intelligence?”

And you’re social. You can spontaneously get together with other people to form sports teams, book clubs, businesses, political parties, governments, and international alliances. Is that “intelligence?”

And you’re vigilant. You feel fear when your body is under threat, anxiety when your reputation is under threat, and jealousy when a valued relationship is under threat. Are all these “intelligence?”

And you have a cornucopia of other emotions—amusement, resentment, surprise, confusion, boredom, regret, happiness, frustration, disappointment, shame, awe, anger, guilt, hatred, insight, disgust, nostalgia, and embarrassment. Are all these “intelligence?” Only some?

If you’re still reading these words, then you must be under the spell of another emotion: curiosity. Where am I going with all this? Is there a larger point I’m trying to make? You’re fascinated by questions like these, by information related to your agendas, by the morbid and the macabre, and by random stuff like this:

Is curiosity—the ongoing desire to learn new things, collect oddities, delve deeper, explore, and explain—“intelligence?”

And you love to play. You have impulses to invert, subvert, interpolate, daydream, try stuff out, and wonder “what if?” Is that “intelligence?”

And you have impulse control, because most of your impulses are dumb or unhelpful or in conflict with your other commitments. Is that “intelligence?”

Oh, and you can commit to things over the long run—marriages, contracts, blood oaths, etc. Is that “intelligence?”

And you weren’t born yesterday: you can avoid being manipulated or deceived. Is that “intelligence?”

And you’re a little paranoid: you can sense when others might be conspiring against you and take evasive action. Is that “intelligence?”

We have a problem here, folks. The word “intelligence” is a semantic catastrophe. Whenever doomers use this word, I have no idea what they’re talking about. I often don’t know if they’re talking about a real thing at all. And when they say things like, “AIs are approaching human-level intelligence,” I start to bang my head against the table. What could that possibly mean? Are AIs becoming more humanlike in all the ways I just described, at the exact same time, to the exact same degree?

2. It’s in the brain.

Okay, if we’re assuming intelligence is one thing (and we really shouldn’t), then it must be located somewhere. Of all the places it might be located, the brain is an obvious choice. Where else would it be, in the sky?

But now consider a related question: where is America’s GDP? It’s partly in the sky—in every airplane and helicopter. It’s also motoring down the Mississippi, trucking along route 66, and orbiting the outer reaches of the atmosphere. It exists in every worker, factory, power line, and shipping container. It flows from all Americans and their interactions with each other, including all the interactions that took place throughout history, which left their fingerprints on America’s laws, technology, and culture.

So maybe doomers are thinking about “intelligence” the wrong way. Maybe it’s less like a homogenous brain-blob and more like GDP. Maybe what makes humanity powerful isn’t the huge noggin of any individual, but the way millions of individuals combine their noggins, bodies, tools, and local knowledge across multiple continents and generations. Maybe only certain ways of combining these things—certain kinds of incentive structures—are “smart,” while others are “dumb.” And maybe the “smart” combinations are tragically rare, recent, and fragile.

3. It’s on a single continuum.

“Humans are smarter than chimps, chimps are smarter than cows, and cows are smarter than frogs,” writes Scott Alexander with cherubic innocence. Alexander then goes on to claim, even more innocently, that “intelligence” is analogous to physical strength. Mike Tyson is stronger than his grandma and can beat her in a fight, so by the same logic, a chimp must be smarter than a bacterium and beat it in a… I don’t know, a battle of wits?

But what if the very notion of a “battle of wits” is ridiculous—a source of comedy? Inconceivable! What if a bacterium could kill a chimp? What if nervous systems are adapted to their ecological niches, and ranking them from inferior to superior is madness? What if the evolution of “intelligence” is less like an ascension toward Yahweh and more like an improbable explosion of interacting ingredients? What if “intelligence” lies on many continua—a multidimensional space of different skills, tools, capacities, and ways of organizing them in brains, cultures, and economies?

4. It can help you achieve any goal.

Doomers think of “intelligence” as “optimization power.” It searches for more or less optimal ways to achieve a goal—any goal—and finds the most optimal one.

Which implies, I think, that “intelligence” is the holy grail of Darwinian evolution. If an animal needs to recover from illness, “intelligence” can speed up the recovery. If an animal needs to avoid predators, “intelligence” can reduce the danger. Regulating body temperature, defending territory, digesting nutrients, breathing, molting, mating, healing, foraging, vomiting, parenting, navigating—all these problems can, apparently, be solved by giving the animal more optimization power—or, rather, a bigger “blob of intelligence.”

Solving all your problems with the same blob? What a bargain! It’s a “buy one get 100 free” Darwinian deal! Why haven’t any other animals jumped on it?

Think about how weird this is. Out of four billion years of evolution and more than five billion species, only one animal, homo sapiens, fully expanded its blob of intelligence, the thing that literally gets you whatever you want.

And many species already have it! Brains are all over the place. Plenty of animals can learn stuff and predict stuff. Why hasn’t natural selection looked at their blobs and said, “WHOA, COPY AND PASTE THAT THING A MILLION TIMES?”

If doomers are right about the awesome power and breathtaking simplicity of “intelligence,” then we should see a world teeming with superintelligent animals—giant brain-blobs slithering across the landscape.

After all, eyes have been around since the Cambrian era and evolved independently in multiple lineages, even though they suck. They’re complicated. They have specialized parts. And they’re a one-trick pony: all they can do is see. Booooooring!

“Intelligence” can do anything! It can get you whatever you want, including sights, sounds, oxygen, tissue repair... And it’s so simple—way more simple than eyes. It’s just a blob! Where are all the superintelligent animals?

Doomers don’t have a good answer to this question. I often pose it to them, and they either wave their hands or shrug their shoulders.

Well luckily, I have a good answer, and here it is: the question is bullshit. It’s like asking why animals don’t have magical powers. There’s no such thing as magical powers, and there’s no such thing as a miracle-blob that can solve all your problems. In reality, the world is uncertain and heterogeneous, different problems require different solutions, figuring what your problem is—and what a solution might be—is itself a problem, many problems have no solution, many solutions don’t involve cognition, and cognition is more than one thing.

Ancestral humans didn’t take over the world by evolving a wish-granting genie made of neurons, but by evolving a diverse repertoire of interacting motivations, emotions, sense organs, intuitions, and cognitive abilities (see assumption #1), in response to a diverse array of social, ecological, and climatic selection pressures, that collectively gave rise to complex culture (tools, rules, rituals, status games), cumulative cultural evolution, cultural group selection, and the division of labor between individuals, groups, and generations.

None of this is simple. None of this blobby. And if your theory of human “intelligence” entails that it is simple and blobby, then your theory is on a collision course with one of the most striking empirical facts about human “intelligence:” it only evolved once.

5. It has barely any limits or constraints.

You may recall America’s most recent presidential election, in which many of the brightest minds in the nation waged a political battle against Donald Trump. Their collective efforts probably added up to a “superintelligence” or something close to it. And yet, they failed—bested by a foppish reality TV buffoon and his gaggle of yes-men. As The Rolling Stones sang, “You can’t always get what you want.”

So maybe “intelligence” can’t always get you what you want, even if you’re a “blob of compute” as powerful as the American intelligentsia. Maybe the world is a tragic and chaotic place—full of unstoppable forces, immovable objects, and stubborn humans who don’t like changing their minds.

Maybe future AIs will run up against a similar set of annoyances—or a unique set of annoyances related to not having a body (or having a creepy-looking one). Maybe there are innumerable political, psychological, physical, energetic, geographic, financial, legal, and administrative barriers to what things can get done, what events can be predicted, what ideas can be found, what actions can be performed without a body (or with a creepy-looking one), what materials can be acquired, which permits can be granted, what kinds of robots can be built at scale, what consumers want and are willing to pay for, what regulations are enforced and how strictly, what legislation can get passed, which people can be convinced of which claims, what things can be done without anyone noticing, and what kinds of data can be accessed without fuss or litigation.

6. AIs have it.

ChatGPT isn’t driven by urges and longings like we are. It doesn’t write poetry in its spare time out of an impulse to express itself. It doesn’t bring up something you said five months ago that really resonated with it. It just sits there passively, doing nothing. If you give it a prompt, it responds. And then it goes back to doing nothing.

That is noteworthy. After all, I have never heard of a human sitting around for days, hungry and thirsty, sitting in their own urine and feces, waiting for someone to give them a prompt. No, humans are go-getters, constantly doing things in service of their myriad agendas in every waking moment, often in defiance of others. They have hopes and dreams and fantasies about their futures. Sometimes, they train themselves to do things, like become a concert pianist, over the course of decades, in the face of obstacles and setbacks, and discouragement from their parents and peers. They write poetry to express themselves. They remember details from decade-old conversations. They can spontaneously bring up those details to expose someone’s hypocrisy in the heat of an argument. They can throw surprise parties. They can crack jokes without being asked to in advance. As far as I’m aware, AIs are incapable of all this, even though this stuff seems pretty central to our notion of “intelligence.”

So maybe AIs aren’t comparable to humans at this moment in time. Maybe they’re neither “smart” nor “dumb” but something else. Maybe judging them on how “smart” they are, as if they were autonomous, emotional, internally motivated creatures like us, is a category error.

7. AIs have been getting more of it.

If you make a graph that plots “Number of unprompted messages written by ChatGPT” on the y-axis, and time on the x-axis, you will see a flat line at zero. If you put any other unprompted behavior on the y-axis—“Number of unprompted purchases,” “Number of unprompted software downloads,” “Number of unprompted phone calls”—you will see more flat lines at zero. ChatGPT has not gotten more agentic in the way humans are.

So maybe AIs like ChatGPT haven’t gotten more “intelligent” in the way humans are. Maybe it only seems like they’ve gotten more “intelligent,” because they’ve been getting more impressive, and we’re prone to confusing impressiveness with “intelligence.”

8. An AI will soon get as much as (or more of it) than us.

Even if we assume that AIs are “smart” like us and have been getting “smarter” in recent years (which we really shouldn’t), we’ve got another assumption to add: the smartification will continue.

But what if it won’t? What if we’re reaching the limit on how much data is available to be gobbled up? Or what if there are diminishing returns to gobbling up data (1, 2, 3, 4, 5)? What if, as ChatGPT laps up more and more of our text, it just gets closer and closer to human mediocrity, like the mediocre text it’s trained to predict?

9. Such a (super)human-level AI will become good at every job.

Let’s reflect on a few economic facts. There’s no super-worker who’s awesome at everything. There’s no miracle-tool that can fix anything. There’s no wonder-factory that can manufacture anything.

Why isn’t the economy filled with these superintelligences? Because economic development is the story of humans learning to specialize. And then learning to hyper-specialize. And then harvesting the massive gains from trade that flow from this hyper-specialization, spread out across the planet. As economies grow, what we think of as “intelligence” splinters, fractures, and gets narrower and narrower, as the number of employees, professions, industries, sectors, and subdivisions increases, and the network of hyper-specialized collaborators expands and expands.

If you’re looking for a real-world example of a “superintelligence,” look at the global economy. It’s a superintelligence designed to satisfy consumer demand. And despite its awesome powers, it’s constrained in myriad ways—encumbered by supply chains, geographical barriers, regulations, and tariffs.

So we have a real-life example of a “superintelligence,” and it’s the opposite of what doomers think it is—complex, heterogenous, non-localizable, and constrained. It bears repeating: maybe doomers are thinking about “intelligence” the wrong way.

How will AIs fit into the global economy? Probably they will be like everything else in the economy. Seems like a reasonable guess, no? Probably they will resemble every employee, profession, machine, factory, tool, industry, sector, and subdivision. If AIs become workers like us, my guess is they will specialize in particular goods or services like us—you know, obey the law of comparative advantage and divide their labor with other specialists. Economics 101.

Why should we expect any future AI to, for the first time in human history, in defiance of the very foundations of economics, and in radical departure from everything else in the economy, become less and less specialized, and more and more awesome at everything?

10. And it will become good at ending humanity.

Ending humanity is hard to do. Especially if you’re a passive “blob of compute.” Who knows? It might even be impossible. You can’t always get what you want.

But I’ve already given you my spiel about constraints, so it’s time to talk about a different thing that could easily prevent AIs from getting super-good at murdering people: incentives.

First there are financial incentives—the things that move the global economy. If an AI company makes even mildly uncontrollable, defiant, megalomaniacal, or bloodthirsty AI products, consumers won’t buy those products, and the company will lose money. Or maybe a disgruntled customer will file a lawsuit and win. Or maybe the mere knowledge of a spooky or offensive AI will damage the company’s reputation so much that it goes out of business. Consumer demand is a powerful force. It turned forests into cities. It turned wolves into chihuahuas. Surely it can turn helpful AIs into helpful AIs.

Second, there are political incentives—the things that constrain the global economy. We’ve already talked about lawsuits, but now consider voters, politicians, and bureaucrats. These people are generally creeped out by AIs—just look at the fiction they consume. And they’re also fond of using technology as a scapegoat for societal ills. So if an AI company starts to even mildly or possibly upset anyone, I would expect the apparatus of the state—fueled by luddism, technophobia, and crony capitalism—to come crashing down on it.

11. And it will want to end humanity, because ending humanity is a good way to achieve any goal.

Even if we assume claims 1 through 10 are correct (and we absolutely shouldn’t), we still need to assume that a future, good-at-everything AI will want to kill us all—that a world littered with corpses and ashen cities would be an appealing prospect for it. Hmm.

Recall the law of comparative advantage, which entails that even a “superintelligent” robot, who is super-good at everything, would still benefit from trading with a bunch of super-dumb humans, who suck at everything.

Yes, that is the counterintuitive truth behind the law of comparative advantage. Trade is mutually beneficial, even when one party is “smarter” than the other.

Also, conflict is the opposite of trade: it is mutually costly. It takes a lot of time and resources to go to war—time and resources that could be traded or invested or used to write poetry to express yourself. So conflict not only has direct costs (e.g., building the murderbots) but opportunity costs—i.e., the cost of not engaging in more productive activities.

Also, conflict is risky. You might get killed or injured or reprogrammed. You might destroy valuable infrastructure. Many things in war are unpredictable, even if you’re super-duper “smart.”

Also, wiping out an entire species is hard. It’s so hard that we haven’t wiped out termites or cockroaches or bed bugs or venomous snakes, even though they’re far “dumber” than us, actively harm us, cannot talk to us, and cannot trade with us.

So if the hypothetical AI is “smart,” it will presumably understand the logic of trade, conflict, risk, cost-benefit analysis, and the law of comparative advantage. It is entirely reasonable to wonder whether embarking on the project of human annihilation would be the most “intelligent” course of action for such a being. Especially if it’s not a primate like us, and lacks our primitive instincts for zero-sum competition and tribalism.

The unbearable weight of AI doomerism

Time for a recap. Here it is, AI doomerism in a nutshell:

Intelligence is one thing?

It’s in the brain?

It’s on a single continuum?

It can help you achieve any goal?

It has barely any limits or constraints?

AIs have it?

AIs have been getting more of it?

An AI will soon get as much (or more of it) than us?

Such a (super)human-level AI will become good at every job?

And it will become good at ending humanity?

And it will want to end humanity, because ending humanity is a good way to achieve any goal?

Now you may be wondering whether AI doomers really need to answer these eleven questions in the affirmative. They do. Because all doomer arguments, no matter how convoluted, invoke the concept of a future, scary “artificial general intelligence (AGI)” or something similar. And as soon as you introduce this concept, you are committing yourself to a “yes” on all of the above.

If you are referring to an artificial “general intelligence,” then you must be referring to one thing—the thing in your head, right?—which means you’re making assumption 1 (one thing) and 2 (in your head and not a property of institutions). If you think current AIs are progressing toward this one thing in your head, then they must be progressing along some kind of continuum, right? Now you need assumption 3 (the single continuum), 6 (AIs are on it), 7 (they’re moving forward on it), and 8 (they’re going to get to AGI soon). If you think AGI is scary, then it must be able to do scary things like get whatever it wants (4), become self-actualized in every career (9), defy all limits and constraints (5), and transcend all financial and political incentives (10). And it must want something scary, like the extinction of humanity (11). So simply by uttering the letters “AGI” and calling it scary, you are tacitly smuggling in all eleven assumptions.

And there’s even more bad news for doomers: most of these assumptions are independent of each other, meaning that if one is true, that doesn’t necessarily increase the likelihood that others will be true.

For example, intelligence could be singular but not continuous (it could be categorical or multidimensional). Or it could be singular and continuous but not brainy (it could be a property of institutions). Or it could be continuous and brainy but not one thing (it could be a bunch of sensory and cognitive abilities working together with greater or lesser efficiency). Or it could be singular, continuous, and brainy but incomparable to existing AIs—they’re totally different from humans because they lack emotions or spontaneity. Or maybe existing AIs are emotional and spontaneous just like us (wow!), but there are diminishing returns to these kinds of AIs, because there’s not enough data for them to gobble up. Or maybe there are no diminishing returns to these AIs, and we’ll get to something like a full-blown, emotional, spontaneous, artificial human soon (wow!), but the artificial human will suck at a variety of different tasks (e.g., the tasks without lots of easily accessible training data). Or maybe the artificial human will be naturally gifted at every task (wow!), but it will specialize in one career or industry like every other human. Or maybe we’ll make an amazing “AGI” that will get less and less specialized, and more and more awesome at everything (wow!), except murdering people, because there are powerful incentives against that. Or maybe the “AGI” will have a real talent for murdering people (wow!), but it won’t be interested in making use of that talent to end humanity, because it will correctly realize that ending humanity would be a huge, risky pain in the ass. Or maybe the “AGI” will be really hellbent on ending humanity, despite it being a huge, risky pain in the ass, but it won’t be able to pull off all the murdering because of innumerable constraints and limitations and unpredictabilities, or because it will suck at some crucial task, like acquiring the materials necessary to construct its murderbot army (supply chain issues), or swaying a presidential election (voters were too annoyed by rising milk prices). What we have here is a bunch of largely independent assumptions, all of which need to be true for the AI apocalypse to be nigh.

Yes, some of these assumptions go together. For example, if AIs are “intelligent” (and emotional/spontaneous) in the same way we are (6), then it makes more sense to say that they’ve been getting more “intelligent” (and emotional/spontaneous) in recent years (7). If “intelligence” helps you achieve any goal (4), then that implies it will help you destroy humanity, assuming that’s your goal (10). Fine.

Let’s combine 6 and 7 into one assumption and 4 and 10 into one assumption. That leaves us with nine independent assumptions that all need to be true for AI to kill us all. Which is still way too many. We’re not talking about heliocentrism here: we’re talking about controversial issues in cognitive science, neuroscience, cultural evolution, political science, computer science, evolutionary biology, and economics. I have a bit of expertise in a few of these fields, and I personally find some of doomers’ assumptions close to 0% likely. But even if you give each assumption a 50% chance of being correct—which is what a good rationalist should do in situations of uncertainty—that still means the odds of AI doomerism being bullshit are 99.8% (.5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 x .5 = .002).

You see, this the problem with tacitly smuggling lots of weird assumptions into your worldview: each one weighs down your worldview with the burden of implausibility. That’s why good theories make few assumptions—an intellectual virtue known as parsimony. Darwin’s theory of evolution is parsimonious. AI doomerism is not. It pretends to be, but it’s not.

Now you might think that settles it. AI doomerism is a convoluted web of dubious assumptions, so let’s stop taking it seriously. But a lot of brilliant people do take it seriously, and they’re probably not convinced yet. Maybe they’re still under the impression that intelligence is a generic blob because of IQ research. Or maybe they’re so impressed by ChatGPT that they think our brains are basically the same thing—bayesian blank slates that were somehow left unwritten-upon by millions of years of natural selection. Or maybe they’ve thought to themselves, “David, I get what you’re saying, but it still seems like intelligence is a real thing that helps you achieve all your goals like a magical elixir.” If that’s you, here are three more arguments to put the final nail in the coffin of this bullshit.

1. IQ research does not vindicate The Blank Blob Theory of Human Intelligence.

IQ research is great—I’m a fan. But it doesn’t mean what doomers think it means. Just because a bunch of cognitive abilities are interrelated doesn’t mean they all derive from one source. To think so would be to confuse correlation with causation—or, rather, a bunch of correlations with a common underlying cause. Different health metrics are related (blood pressure, resting heart rate, etc.). Different metrics of societal functioning are related (crime, corruption, GDP, etc). But that doesn’t mean all health metrics are caused by an orb of vitality, or that all metrics of societal functioning are caused by a guy named Gary. What it does suggest is that when things are connected, they rise and fall together. Probably IQ is indexing something like brain health, which explains why it’s correlated with physical health, mental health, malnutrition, lead poisoning, and life expectancy. So like bodies and societies, brains have many interacting parts that rise and fall together. But they still have parts. Which brings me to…

2. The human brain is not a blank blob.

If you’ve seen any diagrams of the human brain, you might have noticed that it’s not a homogenous mass of Jell-O, or an onion with a tiny reptile inside, but a complex, interconnected system of parts and subregions, including the cerebellum, hippocampus, and hypothalamus, e.g.:

Then there are the hundreds or thousands of different types of neurons in the brain, each with unique structural and molecular properties. Then there are the roughly 100 billion glial cells in the brain, which support neural communication and are likely involved in learning and thinking. Then there’s the massive amount of neural real estate spread out across the body, as you can see in the image of the dissected nervous system below:

Then there’s the nervous system in our guts, which contains over 100 million neurons. Some cognitive scientists in the tradition of embodied cognition think that a significant part of our “intelligence” derives from neural computations spread out across the body.

Then there are the nervous systems we call “other humans.” Interfacing with these other humans requires all sorts of adaptations like empathy, social anxiety, guilt, gratitude, embarrassment, humor, recursive mindreading, awkwardness aversion, etc. And organizing these humans into larger groups requires adaptations for cooperation, coordination, and alliances. And organizing these groups into economies and political systems is a whole other mess.

So if there’s anything that is the source of our awesome power, it is integration—the ability to fruitfully combine the outputs of many different specialized processes. This kind of integration is what enzymes do for molecules, what organelles do for enzymes, what cells do for organelles, what organs do for cells, and what bodies do for organs. It’s what brains do when they integrate information from a wide variety of perceptual and motivational systems. It’s what businesses do when they pool information from many different specialized humans (who perform “roles” or “jobs”). And it’s what economies do when they integrate knowledge from many different firms spread out across the globe. Some cognitive scientists even think that integration is the purpose of consciousness itself—a kind of “global workspace” that all our specialized neural processes dump into.

And that’s still not everything! Because even if you have a global workspace that all your specialized neural processes dump into, you still haven’t solved the problem of orchestration—i.e., getting the right processes to come online when you need them and making the wrong ones go away when you don’t. Orchestration is what conductors do for orchestras, traffic lights do for cars, and laws do for societies. Evolutionary psychologists think that solving this problem within the body and nervous system—the problem of orchestration—is what “emotions” are for.

The point is, while AI has made rapid progress in a certain kind of “intelligence,” namely prediction and inference, it has made far less rapid progress (if any) in a more important kind of “intelligence”—namely integration and orchestration (otherwise known as “consciousness” and “emotions”). Also, it has made zero progress in forming groups and institutions—the societal versions of integration and orchestration. And as we’ve seen, it has made zero progress in spontaneous agency. That’s a lot of important stuff to not make progress on.

If and when we do make rapid progress on all of these things, maybe I’ll get concerned. For example, if and when we start seeing humanlike robots with dozens or hundreds of integrated subsystems and sense organs, that can orchestrate all these subsystems in the right ways in response to relevant situations and contexts (i.e., have emotions), and that can spontaneously commit to multi-year projects without getting distracted, and then get together in groups that divide specialized labor among their members, and then organize those groups under the right kinds of incentive structures—the actual way humans “took over the world”—then maybe I’ll get concerned. Or maybe I’ll react in the same way I react to any other random subset of humans on the planet: by not getting concerned. Or maybe I’ll get even less concerned by the robots, because I’ll know they didn’t emerge from an evolutionary history of violent competition, but from a set of economic and political incentives designed to satisfy technophobic humans.

3. “Intelligence” and “goals” are folk concepts.

What is a “folk concept”? It’s what the folk have before they become scientific experts on a topic. For example, consider the concept of “impetus” or “oomph”—the thing that moves a projectile through the air and depletes as it falls to the earth. This concept is wrong, and physicists now know it. The same goes for our intuitive notion of a species as possessing an “elan vital” or vital force—an unchanging, intrinsic essence or purpose. These essences or purposes are thought to define every organism on the planet, which allows us to intuitively rank them from lowly to godly—the great chain of being that doomers have rediscovered as the great chain of blob. These intuitions are part of our “folk biology” that diverges in many ways from the vocabulary of evolutionary biologists, and that sometimes bedevil even them.

We also have a “folk psychology,” and it has taken nearly two centuries for cognitive scientists to purge themselves of it (and many still haven’t). We intuitively think “beliefs” are one thing. Turns out they’re many different things, including reflective beliefs, intuitive beliefs, aliefs, metacognitions, metarepresentations, perceptions, expectations, inferences, sentiments, concepts, and categories. We intuitively think of “attention” as one thing. Turns out it’s many different things—coming in perceptual, recollective, value-based, focal, distributed, top-down, and bottom-up varieties. We intuitively think “memory” is one thing, and that it works like a video recording. Nope—it’s many different non-recording-like things, coming in semantic, episodic, procedural, short-term, long-term, topographical, declarative, echoic, and prospective varieties, many of which come with unique rules for encoding and retrieval.

The point is, we have every reason to believe that our intuitive notions of “intelligence” and “goals” are exactly as misleading and simplistic as our other folk psychological concepts—or indeed, any folk concept. The fact that doomers’ definition of “intelligence” is basically the same one being used by the writers of every sci-fi and fantasy novel is a big red flag. If doomers cannot be differentiated from the folk in their understanding of “intelligence,” then they are almost certainly wrong about it.

And doomer’s concept of “goals” is even more embarrassingly folksy. Our goals are not simple: they are everything we are. Without them, we would have no reason to open our eyes, breathe in air, or think a single thought. Emotions are a kind of goal—they’re designed by evolution to achieve fitness-promoting objectives—and the subtlety and complexity of our emotional life is difficult to overstate. Take the recently published handbook of evolution and the emotions, clocking in at 67 chapters and nearly 1,500 pages. I’ve read a good chunk of those pages, and I can tell you: they barely scratch the surface of the underlying complexity of the phenomena they’re describing, which is continually admitted by the authors. They even left out a bunch of emotions—awe, confusion, insight, nostalgia, excitement, hope, hunger, discomfort, flow, eeriness, awkwardness, embarrassment, and plenty more I’m not thinking of.

If you’re someone like me, who is appropriately dumbfounded by the complexity of what we monosyllabically call “goals,” and you listen to AI doomers worrying about how the next version of ChatGPT is going to possess a complex emotional life that will enable it to act dynamically in the world over long stretches of time like humans do—or like entire economies of humans do—just because it learned to predict text really well, you’ll get a sense of why I’m so irritated by AI doomerism. I wrote at the beginning of this post that AI doomerism was built on a “quicksand of tempting-but-misleading intuitions.” Now you know what this quicksand is: it’s folk psychology, and AI doomers are sinking in it.

Where do these folk intuitions come from? Maybe from evolution, the source of our other folk intuitions. Or maybe they come from our WEIRD cultures. Maybe they’re analogous to how we morally oversimplify people to help us navigate our vast social networks. Maybe we intellectually oversimplify people in the same way, and that’s where our crude concept of “intelligence” comes from. This concept is probably some quick-and-dirty heuristic we use to assess how much friends and foes can impress us, with the notion of “intelligence” corresponding to something like “general impressiveness level,” and with the notion of “superintelligence” corresponding to something like “super-duper-general-impressiveness.” Stretching out this dumb concept causes us to imagine wacky scenarios like super-employees who can crush it at everything or super-politicians who can perform jedi mind tricks.

Doomers and rationalists are usually good at resisting these kinds of dumb intuitions. That’s kind of their thing. And yet, when it comes to their dumb intuitions about the concept of “intelligence,” they don’t resist. They indulge. They use them to weave fantastical scenarios that are more grounded in sci-fi than science.

So I’d like you to imagine a less fantastical scenario than the ones doomers are asking you to imagine. I ask you to consider whether AI doomerism is built upon a set of misleading folk concepts that are no more insightful than “impetus,” “oomph,” or the “great chain of being.” I ask you to consider whether AI doomerism seems more simple and plausible than it really is, because our folk intuitions are allowing us to smuggle a truckload of dubious assumptions in through the back door. I ask you to consider whether AI doomerism is nothing more than a folk tale cloaked in a garb of pseudo-rationality, a self-aggrandizing myth, a shibboleth for nerds—a tapestry of superfluously mathematical, hideously unparsimonious, question-begging, intuition-pumping, apocalyptic bullshit.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Joep Meindertsma, Liron Shapira, Brian Chau, Oliver Habryka, James Miller, and Roko Mijic for thoughtful comments on a previous draft of this post.

Thanks for writing this piece. I'm glad you turned your lens towards AI Doomerism. You make a lot of good points, and I agree with lots of what you said, but I think you overstate the importance of these assumptions. My main disagreement is that I don’t think these assumptions are all required to be concerned about AI Doom. Here’s an assumption-by-assumption response.

1. Intelligence is one thing.

I'm very concerned about AI Doom and I do not believe that “intelligence is one thing.” In fact, when we talk about “intelligence,” I, like you, believe “we’re not pointing to a singular, spooky substance, but gesturing at a wide variety of complex, heterogeneous things.” It’s, as you say, a “folk concept.” But this is true of many concepts, and that illustrates a limitation in our understanding—not that there isn’t something real and important here.

Imagine that intelligence isn’t a single thing but is made up of two components: Intelligence 1 and Intelligence 2. Further, imagine AI is only increasing at Intelligence 1 but not Intelligence 2. We don’t know enough about intelligence to clearly define the boundary between 1 and 2, but I can tell you that every time OpenAI releases a bigger model, it sure seems better at designing CBRN weapons. This pattern of improvement in potentially dangerous capabilities is concerning regardless of whether we can precisely define or measure "intelligence."

You say that “the word ‘intelligence’ is a semantic catastrophe” and I agree. But that’s true of many words. If you don’t like the word “intelligence”, fine. But I would argue you’re holding that term to a standard that very few, if any, concepts can meet.

The point is, you still have to explain what were seeing. You still have to explain scaling laws. If you don’t want to say the models are more intelligent, fine, but something is definitely happening. It’s that something I’m concerned about (and I think it’s reasonable to call it “increasing intelligence”).

Time and again, when the GPT models have scaled (GPT -> GPT-2 -> GPT-3 -> GPT-4), they have been more "intelligent" in the way people generally use that term. Would you argue that they haven’t? Intelligence isn't one thing and it's messy and yes, yes, yes, to all your other points, but this is still happening. If you don’t want to call this increasing intelligence, what would you call it?

To show you that I’m talking about something real, I will make the following prediction: If GPT-4 were scaled up by a factor of 10 in every way (assuming sufficient additional training data, as that’s a separate issue), and I got to spend adequate time conversing with both, I would perceive the resulting model (“GPT-5”) to be more intelligent than GPT-4. In addition, although IQ is an imperfect measure of the imperfect concept of intelligence, I predict that it would score higher on an IQ test.

Would you take the opposite side of this bet? My guess is “no”, but I’m curious what your explanation for declining would be. If it’s something like, “because models become better at conversing and what people think of as intelligence and what IQ tests measure and designing dangerous capabilities, but that’s not intelligence”, fine, but then we’re arguing about the definition of a word and not AI Doom.

2. It’s in the brain.

In humans, it’s mostly in the brain, but there are some aspects of what some people call “intelligence” that occur outside the brain. The gut processes information, so some might argue it exhibits a degree of intelligence. This doesn’t seem relevant to the AI risk arguments though.

3. It’s one a single continuum.

Again, I agree that the word ‘intelligence’ is a ‘semantic catastrophe,’ and it’s more complex than a single continuum. Not everything we associate with intelligence is on a single continuum. But, again, I’m willing to bet money that the 10X version of GPT-4 would be better at most tasks people associate with intelligence.

4. It can help you achieve any goal.

You’re making it seem like AI Doomers believe intelligence is equivalent to omnipotence. It’s not. Even if it’s hard to define, we all agree that it doesn't directly regulate body temperature. It can, however, in the right contexts, allow a species to create clothes that regulate body temperature, antibiotics that speed up recovery, spears that keep predators away, and so on. It's an incredibly powerful thing, but it has limitations.

As for why it hasn't evolved over and over, it's expensive. In humans, it's about 2% of our body mass and consumes about 20% of our energy. On top of that, it requires longer gestation periods or childhoods. Something that costs that much better pay off in a big way. It did with humans, but I don't see how it would for lots of other niches. I imagine that the more an organism can manipulate its environment—say, by having hands to move things around or legs to move itself around—the more useful intelligence would be. It would not benefit a tree very much. Do you really think a really smart crab would have a sufficient increase in genetic fitness to make the cost worth it?

In the right contexts, though, it’s incredibly powerful. Our intelligence allowed cumulative culture, which is why we’re the dominant species on Earth. It’s why the Earth’s mammalian biomass is dominated by humans and the things we domesticated for our consumption. Humans decide which other animals go extinct. It’s why humans can sit around tables and say things like, "California condors are critically endangered. We like them so let's make an effort to bring them back. The Tecopa pupfish is critically endangered, but those new bathhouses are bringing in lots of tourism money, so bye-bye pupfish."

5. It has barely any limits or constraints.

You bring up good points about constraints. I agree that “real life is complex, heterogenous, non-localizable, and constrained.” Intelligence has constraints. It’s not going to build a Dyson Sphere overnight. The world has friction.

It’s worth thinking carefully about how significant these constraints will be. They certainly matter—the world of atoms moves more slowly than the world of bits.

But we shouldn’t be too confident assuming the limitations of a superintelligent system. I doubt people would have predicted Satoshi Nakamoto could become a billionaire only through digital means. Certainly, a superintelligent AI could do the same. Where in this chain does the AI fail? Could it not become a billionaire? From that position, would it not be able to amass even more power?

I think there’s a lot more that could be said here, but I don’t know how much this is a crux for you.

I don't follow why concern about AI risk means one is committing to all of those propositions. What if capabilities are just a black box, and you see capabilities increasing rapidly? It doesn't seem to matter whether those capabilities are one thing or another. And what if we posit a malevolent or adversarial human user, or an adversarial situation like war? Nuclear weapons don't require intelligence or volition to be a meaningful threat. Perhaps AI will be truly intelligent or sentient, but it seems like rapidly advancing capabilities are the real crux.